Just transition corporate governance and oversight

Since the plans implemented by businesses over the coming years will be pivotal to the world’s decarbonization journey, leadership and governance are also key considerations when analyzing just transition plans. Decision-makers who fail to consider the social dimension of the transition may undermine the achievement of climate action ambitions and could face certain risks like reputational risk. Thus, strong leadership and governance across businesses is an important consideration to appropriately manage risks and leverage opportunities. To drive positive outcomes, corporate boards need to take a proactive role to ensure a just transition is a business priority.

What does a just transition look like in practice?

There are various micro and macro examples of climate transition plans that have failed or may fail due to the lack of a just transition plan. Others have succeeded or appeared poised to succeed because they were able to balance social and environmental considerations. These examples span both emerging and developing markets, highlighting that the just transition is a universal challenge to companies in all geographies. A few examples are described below.

Company case studies

Air Products

Air Products, an American chemical company, is developing a large new green hydrogen project in an area in Texas that’s experienced economic decline due to a recent coal plant shutdown. This project has been aided by the new Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) legislation in the US, which includes green incentives, but it’s a good example of finding a community that has an industrial skillset that can be retrained to enable a greener future.

Enel

This company employs approximately 75,000 people worldwide with 36,000 in Italy. Enel faced up to the challenge of the energy transition and the EU’s tightening emissions limits by announcing the Futur-e Program, an initiative to close and repurpose legacy fossil fuel assets. In May 2017, it announced the closure of two large coal power plants by 2018 and a plan to close all its coal and lignite generation plants by 2030. Along with a 2050 carbon neutral target, ENEL announced the reconversion of 23 power stations with significant employment implications. The unions have always taken a very critical view of the “Future-e” plan and have been critical of the lack of information and their scarce involvement in these processes.

As a result, ENEL entered a social dialogue on a just transition framework agreement with its Italian union partners covering retention, redeployment, re-skilling and early retirement. It provides an example of a just transition plan that included provisions for recruitment using apprenticeship to ensure the knowledge transfer from elderly to younger workers. It also encourages mobility and training to optimize internal resources and dedicated training measures to ensure qualification and employability for the development of its new business.

Engie Australia

In November 2016, Engie announced the decision to close the Hazelwood Power station to reduce its carbon emissions. The state government responded by establishing the Latrobe Valley Authority (LVA) which began to engage unions, Engie and other power station owners, local government and community organizations. Four major initiatives evolved for assisting impacted workers and their families:

- A Worker Transition Service to provide one-on-one transition services and skills development

- Financial support for retraining workers directly employed by Engie and federal government training support for contract workers

- A “Worker Transfer” scheme, to open jobs by launching early retirement schemes at other power stations in the sector

- Regional revitalization with state government establishing a “special economic zone” with financial incentives to companies for creating jobs for displaced workers

Ford automotive

Ford announced plans to cut 1300 jobs in the UK over the next two years, and 3800 jobs across Europe, nearly 2800 of which are engineering jobs. Just one day before its European layoff, Ford announced an investment of $3.5 billion in a new electric vehicle (EV) battery plant in Michigan. Without a retraining or relocation program for these workers, Ford risks lowering morale and talent retention across its workforce, especially its skilled employees, in addition to potential strikes by unions in Germany and additional political intervention in its restructuring program. Growing concern for the auto industry’s impact on workers in its shift from ICE to EV could impact the industry’s ability to attract subsidies.

Solar supply chain

Almost half of polysilicon used to make photovoltaic panels for the solar industry is produced in China. Import bans driven in part by human rights concerns could significantly slow down the uptake of solar required for the energy transition. Siemens CEO Roland Busch warned in December 2021 that “If [forced labor] bans are issued, these could mean that we can no longer buy solar cells from China — then the energy transition will come to an end at this point.” Can the concerns around human rights enable the development of an alternate solar supply chain in countries like India?

Just Energy Transitions Partnerships (JETPs)

At the country level, Just Energy Transitions Partnerships (JETPs) are emerging initiatives aimed at bridging the gap between developed and developing nations in moving towards clean energy.

JETPs are financing mechanisms. In a Partnership, wealthier nations fund a coal-dependent developing nation to support the country’s own path to phase-out coal and transition towards clean energy while addressing the social consequences.1 They involve mechanisms intended to help a selection of fossil fuel-dependent emerging economies make a just energy transition within their self-defined pathway with minimal disruption to their economic development.

JETPs are a nascent concept and are still very much in the process of developing as they are being created through ongoing experience rather than from preexisting frameworks. While JETPs are worth monitoring, we do not yet have enough information to meaningfully engage with stakeholders that have a critical role in helping the JETPs be accepted and effectively implemented. It also remains unproven how JETP partnerships translate into national climate policy changes, which is required for sustained climate progress by countries and companies.

Early progress of the JETP in countries like Indonesia highlight how the program could be more material going forward.

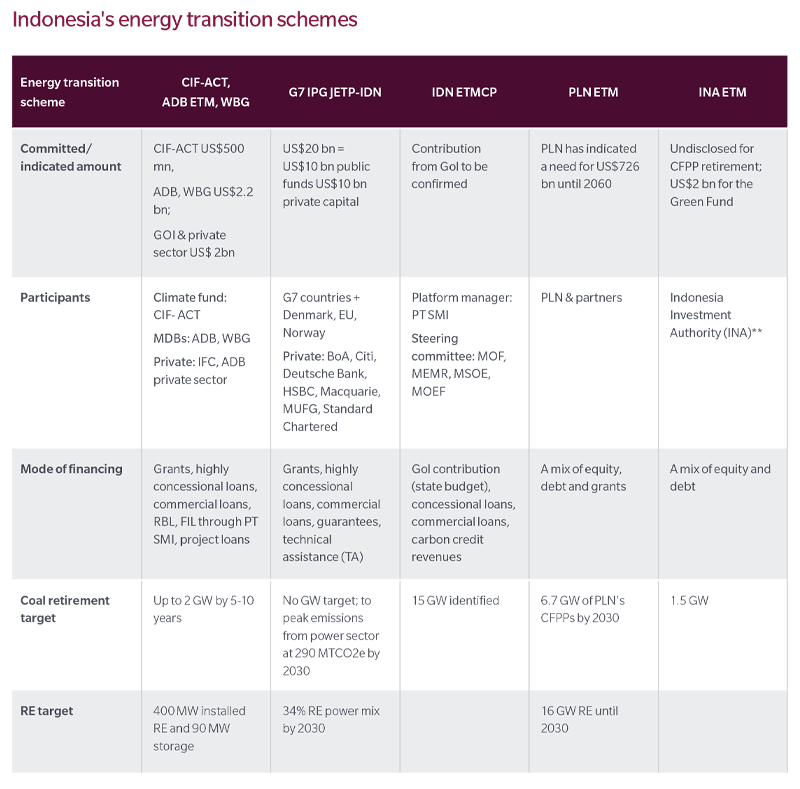

Indonesia

At the end of 2022, Indonesia was offered a $20 billion package from an even mix of public and private capital, with partners including the US, UK, Italy, Norway, Japan, Canada, Denmark, France and other developed nations. While no formal investment plan has been published yet, the stated aims of the JETP are to accelerate Indonesia’s coal phase out which would peak its total power sector emissions by 2030 while also establishing a goal to reach net zero emissions in the power sector by 2050, bringing forward the country’s net zero power sector emissions target by ten years. The plan would also accelerate the deployment of renewable energy so that renewable generation comprises at least 34 percent of all power generation by 2030.

While this $20 billion package represents a small piece of the $600 billion required to fully decarbonize the country’s power sector, it is a precursor of the type of support that may be forthcoming from private and public sources.

Ultimately, the scalability of programs like JETPs will be worth monitoring as they will depend on whether emerging countries can create a credible just transition plan. While corporate success or failure in the transition is heavily dependent on national policy, corporate willingness to participate in the transition could determine whether they can stay ahead of the curve.