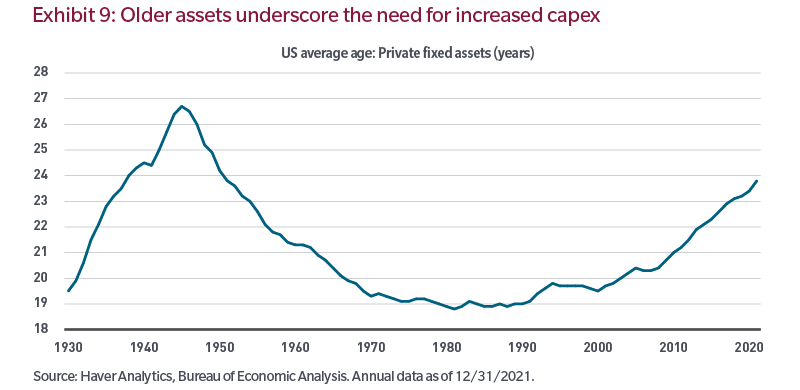

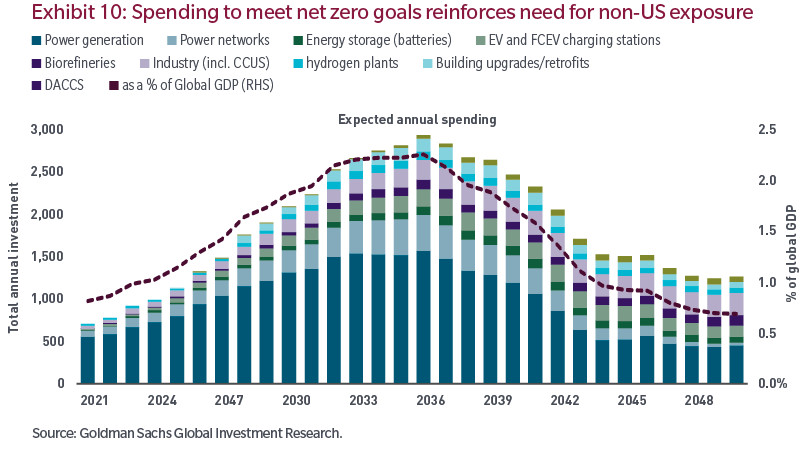

Spending to localize production

The pandemic and the war in Ukraine, among other geopolitical considerations, have revealed the downside of just-in-time inventory systems and global supply chains. While it will take time for localization to play out, many companies are now beginning to reshore supply chains and improve their dependability and resilience. Moreover, this trend is less about US versus non-US and more about specific companies around the globe. We think that the companies that can enable change and provide solutions during this transition will be the long-term winners here, whatever their domicile.

Conclusion

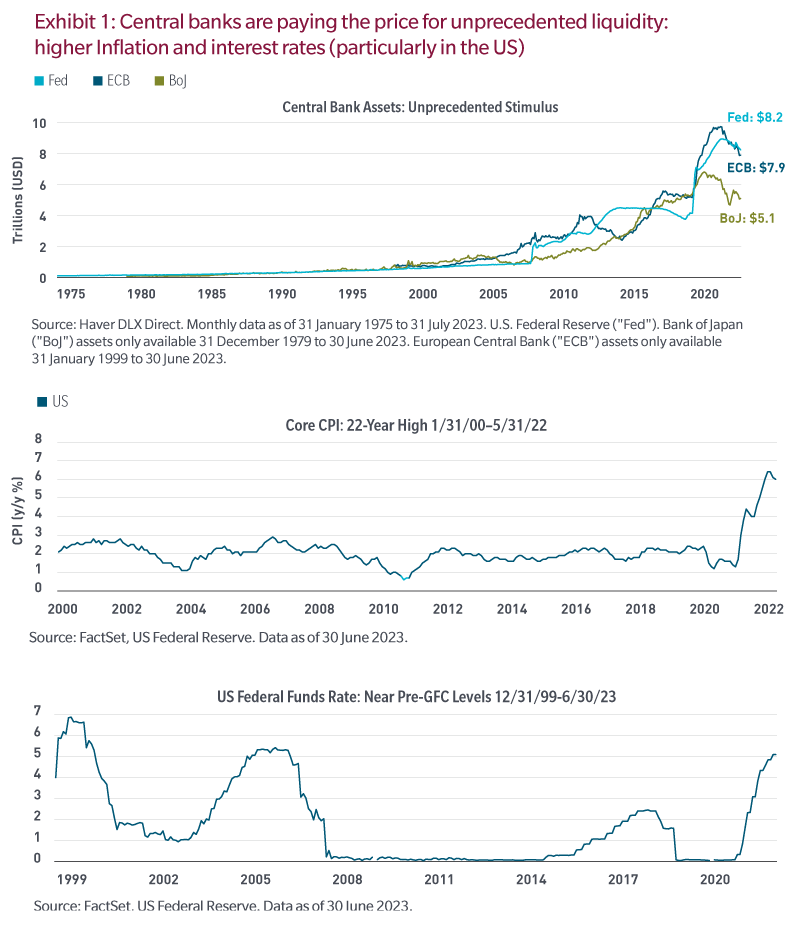

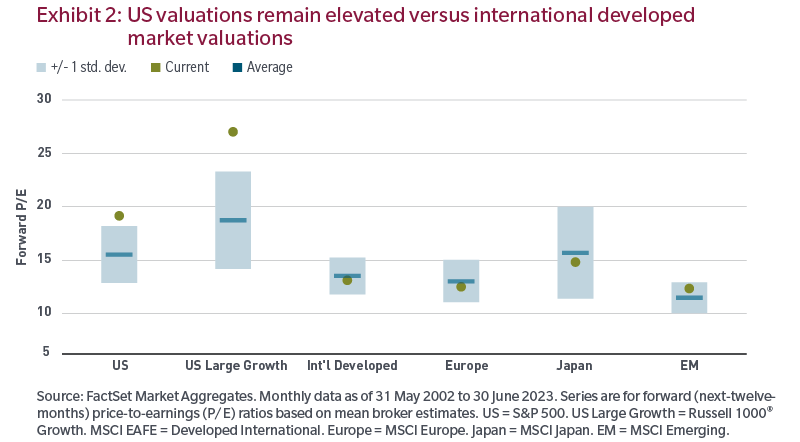

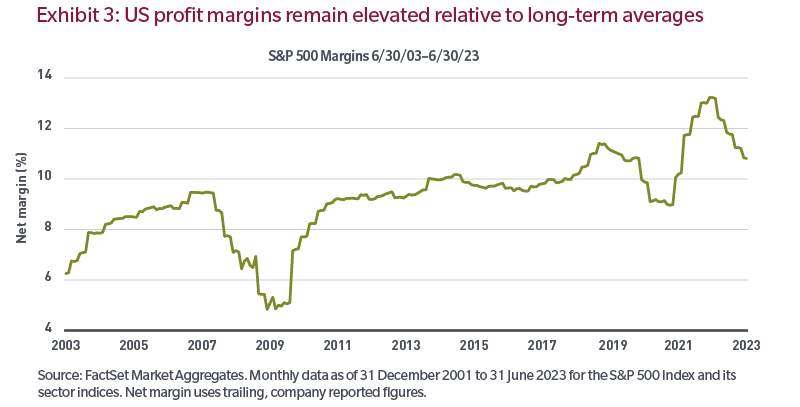

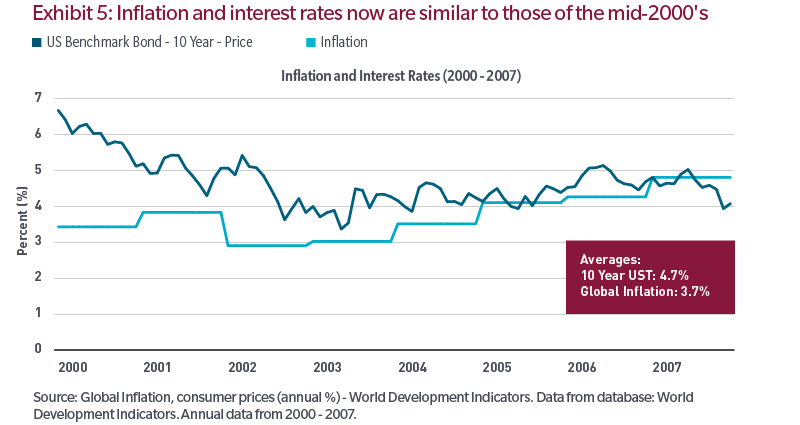

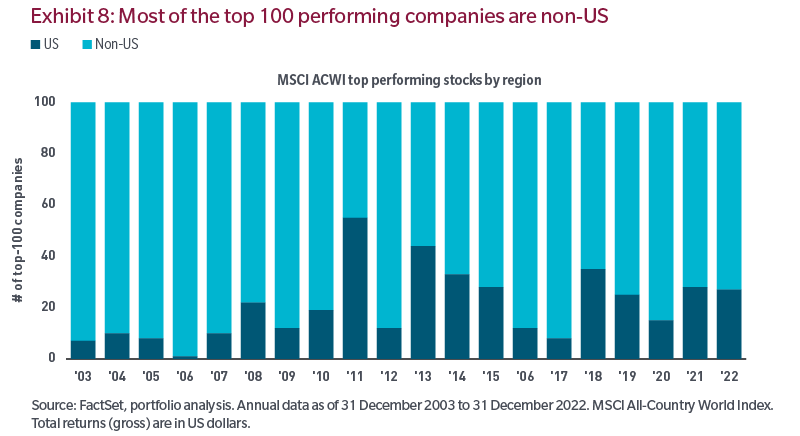

The starting point for markets today is quite different from that of ten years ago. The beta-driven environment in which investors need only pick the right style, region, country or factor is likely over. Today, rates and inflation are elevated compared to the past decade, US valuations remain expensive by historical standards and in some markets, margins are likely still too high. In our view, alpha matters in this environment, not beta. Investing in the best companies globally instead of relying on the mindset of the past decade can potentially help maximize returns while providing the benefits of diversification.

Endnotes

1 Goldman Sachs Global Equity Strategy, 2022 Outlook: Getting Real, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research.

The views expressed are those of the speakers and are subject to change at any time. These views are for informational purposes only and should not be relied upon as a recommendation to purchase any security or as a solicitation or investment advice from the Advisor. No forecasts can be guaranteed. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

“Standard & Poor’s®” and S&P “S&P®” are registered trademarks of Standard & Poor's Financial Services LLC (“S&P”) and Dow Jones is a registered trademark of Dow Jones Trademark Holdings LLC (“Dow Jones”) and have been licensed for use by S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC and sublicensed for certain purposes by MFS. The S&P 500® is a product of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC and has been licensed for use by MFS. MFS’s Products are not sponsored, endorsed, sold or promoted by S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, Dow Jones, S&P, or their respective affiliates, and neither S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, Dow Jones, S&P, their respective affiliates make any representation regarding the advisability of investing in such products.

Index data source: MSCI. MSCI makes no express or implied warranties or representations and shall have no liability whatsoever with respect to any MSCI data contained herein. The MSCI data may not be further redistributed or used as a basis for other indices or any securities or financial products. This report is not approved, reviewed or produced by MSCI.

Frank Russell Company (“Russell”) is the source and owner of the Russell Index data contained or reflected in this material and all trademarks, service marks and copyrights related to the Russell Indexes. Russell® is a trademark of Frank Russell Company. Neither Russell nor its licensors accept any liability for any errors or omissions in the Russell Indexes and/or Russell ratings or underlying data and no party may rely on any Russell Indexes and/or Russell ratings and/or underlying data contained in this communication. No further distribution of Russell Data is permitted without Russell’s express written consent. Russell does not promote, sponsor or endorse the content of this communication.