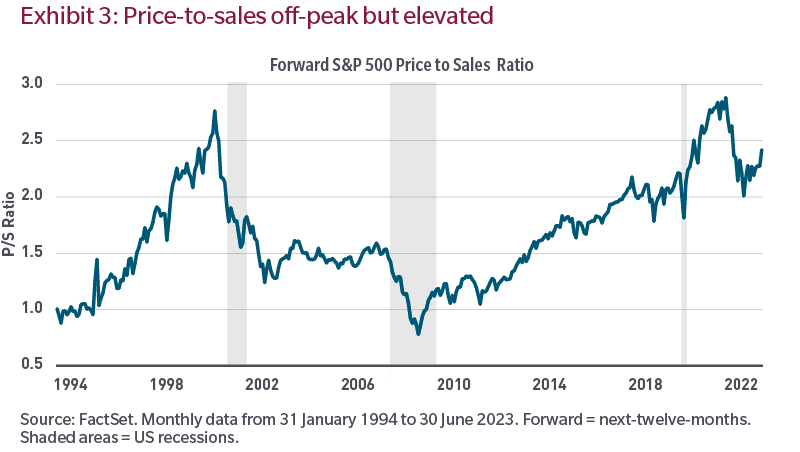

As noted earlier, despite the high-growth era of the 1990s, equities were expensive even on this growth-dependent metric. Not surprisingly, given how weak the economy and sales growth were throughout the post-2008 business cycle, we saw the ratio expand and reach peaks last seen at the height of the internet bubble. Price-to-sales-fell some in 2021 due to the post-lockdown growth that resulted from fiscal and monetary stimulus, which has since faded and why the ratio is re-accelerating, as stock prices have risen in 2023.

Conclusion

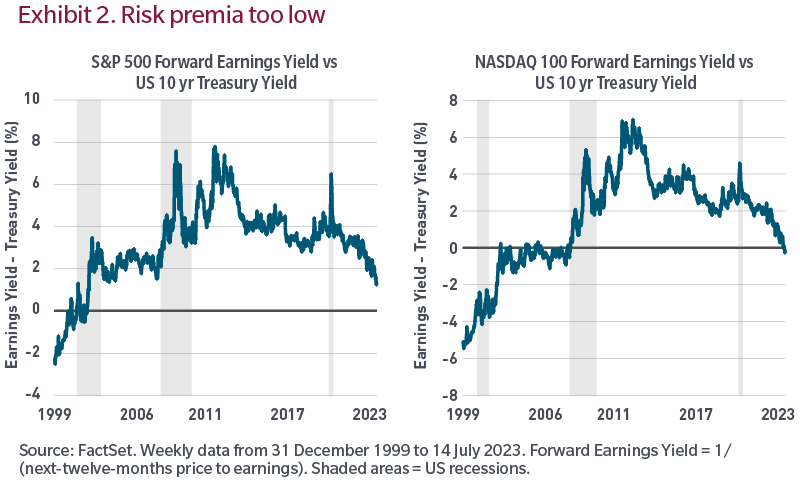

Equities are expensive on traditional valuation measures. The bigger picture, however, is more nuanced. The regime of low capital costs has ended as accumulated debt levels will need to be financed at higher cost, pulling down free cash flow. The cheap labor regime has ended. And the regime of over-stretched supply chains and underinvestment in cleaner (energy) ways of running businesses has ended.

Back to Mr. Box’s axiom about models being wrong but some useful, I think of valuation similarly. Every business cycle and market environment is different, and these idiosyncrasies influence the usefulness of various valuation metrics and are why a broad mosaic of valuation inputs, and understanding the flaws in each, can be instructive.

We have begun a new regime. A regime where capital and labor are scarcer than any point since 2009. A regime where not all companies will be able to outearn their new or normalized input costs. A regime of higher loan and bond defaults, capital restructurings and bankruptcies. The tools necessary to successfully navigate the current regime are quite different from the last. As Mr. Box might have suggested, recognize that all valuation and fundamental models are broken, but some are still useful. Investors will need to do a lot more homework and may find it advantageous to use a mosaic of not only valuation, but also fundamental tools, to help guide the way through this cycle.

The price-earnings ratio is calculated by dividing a company’s share price by its earnings per share.

The price to sales ratio measures the value of a company in relation to the total amount of its recent annual sales.

The S&P 500 Index measures the performance of the 500 largest US publicly traded companies in the US equity market.

The Nasdaq 100 is an index of the hundred largest non-financial stocks listed on the NASDAQ stock exchange.

“Standard & Poor’s®” and S&P “S&P®” are registered trademarks of Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC (“S&P”) and Dow Jones is a registered trademark of Dow Jones Trademark Holdings LLC (“Dow Jones”) and have been licensed for use by S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC and sublicensed for certain purposes by MFS. The S&P 500® is a product of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, and has been licensed for use by MFS. MFS’s Products are not sponsored, endorsed, sold or promoted by S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, Dow Jones, S&P, or their respective affiliates, and neither S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, Dow Jones, S&P, their respective affiliates make any representation regarding the advisability of investing in such products.

The views expressed are those of the author(s) and are subject to change at any time. These views are for informational purposes only and should not be relied upon as a recommendation to purchase any security or as a solicitation or investment advice. No forecasts can be guaranteed.